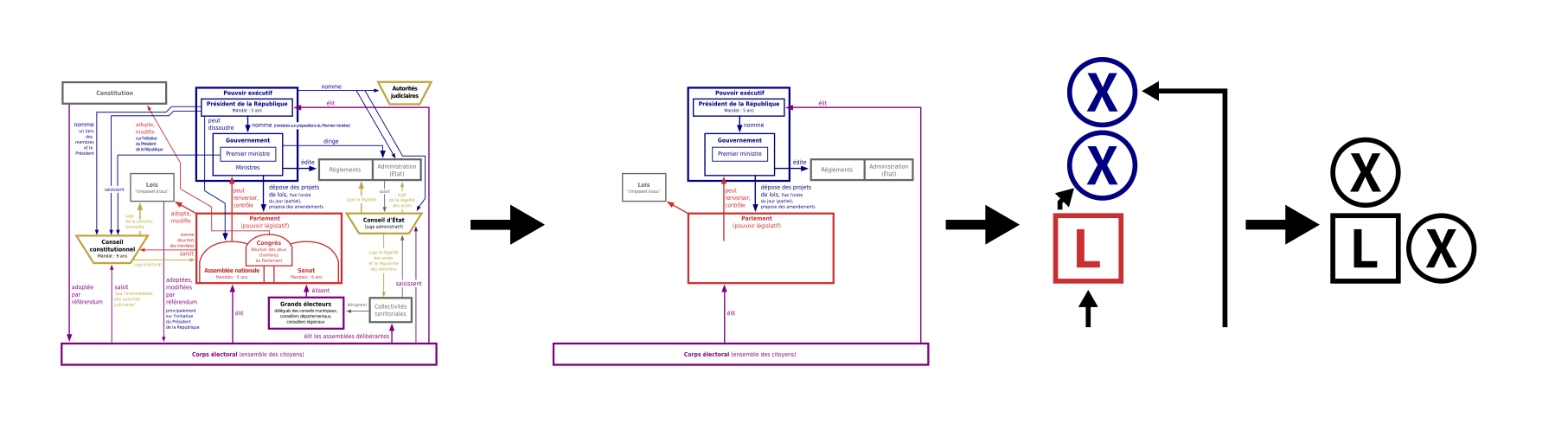

There are a lot of forms of government. Let’s simplify them, abstract them down to find the big categories (and also find what we might be missing).

I will progressively give a list of rules and constraints for this abstraction, the caveats they imply, and sometimes the results of loosening a rule.

Abstractions

First major abstraction: we will only consider executive and legislative. Judicial is a whole other thing (often not considered anyway), and ceremonial roles can be ignored for now; the goal here is to simplify, otherwise government diagrams already exist.

Second major abstraction: only one type of relation is considered: election/designation, meaning one institution determining the member(s) of another. An important detail about this will be given later.

Third major abstraction: only two properties will be shown for each institution. These are:

- Their composition (single person, or council)

- Their powers (legislative, executive)

The constraints

From here we can simply enumerate all possible forms. At this point there are still a lot (in fact, an infinite amount), so let’s restrict them to a certain set of realistic constraints to get a list of real-world possibilities:

Constraint 1: The legislative power is always vested in a council (by definition of legislative and executive; only exception is dictatorship);

Constraint 2: The executive power may be vested in a person or a council, and may be split between institutions;

Constraint 3: Two institutions elected by the same body cannot be of both the same composition and the same powers (to avoid duplicates);

Constraint 4: An institution cannot elect another with the same powers (it would be redundant, as it is usually considered a delegation of powers);

Constraint 5: There has to be one legislature, and at least one executive (cameralism is irrelevant here);

Corollary of constraints 3, 4, and 5: There can only be one or two executives.

Consequences

The executive may be:

- Elected by the legislative council;

- Elected separately from the legislative council;

- In two institutions, one elected by and one separately from the legislative council;

- Merged with the legislative council;

- In two institutions, one merged with the legislative council and one elected separately from it.

All institutions can be represented schematically:

- A person is a circle ◯, a council is a square □;

- The letter means the power, L for legislative, X for executive;

- Putting above means elected by, putting next to means elected separately from, so no need to draw arrows.

Caveats

There are a couple caveats I need to get out of the way before continuing.

Caveat 1: This does not take into account the fact an institution may be nominated by several others (not just one). In this case, it will be counted as being properly designated from a single source (whichever has the most power in determining faction control). I will later introduce a looser version of this rule for special cases.

Caveat 2: Groups such as councils of ministers may be counted as either individual or council, depending on these rules: if a single person or a single coalition agreement gives the direction it is to be counted as single-person, while if it behaves as a genuinely collegial body it is to be counted as a council.

The forms of government

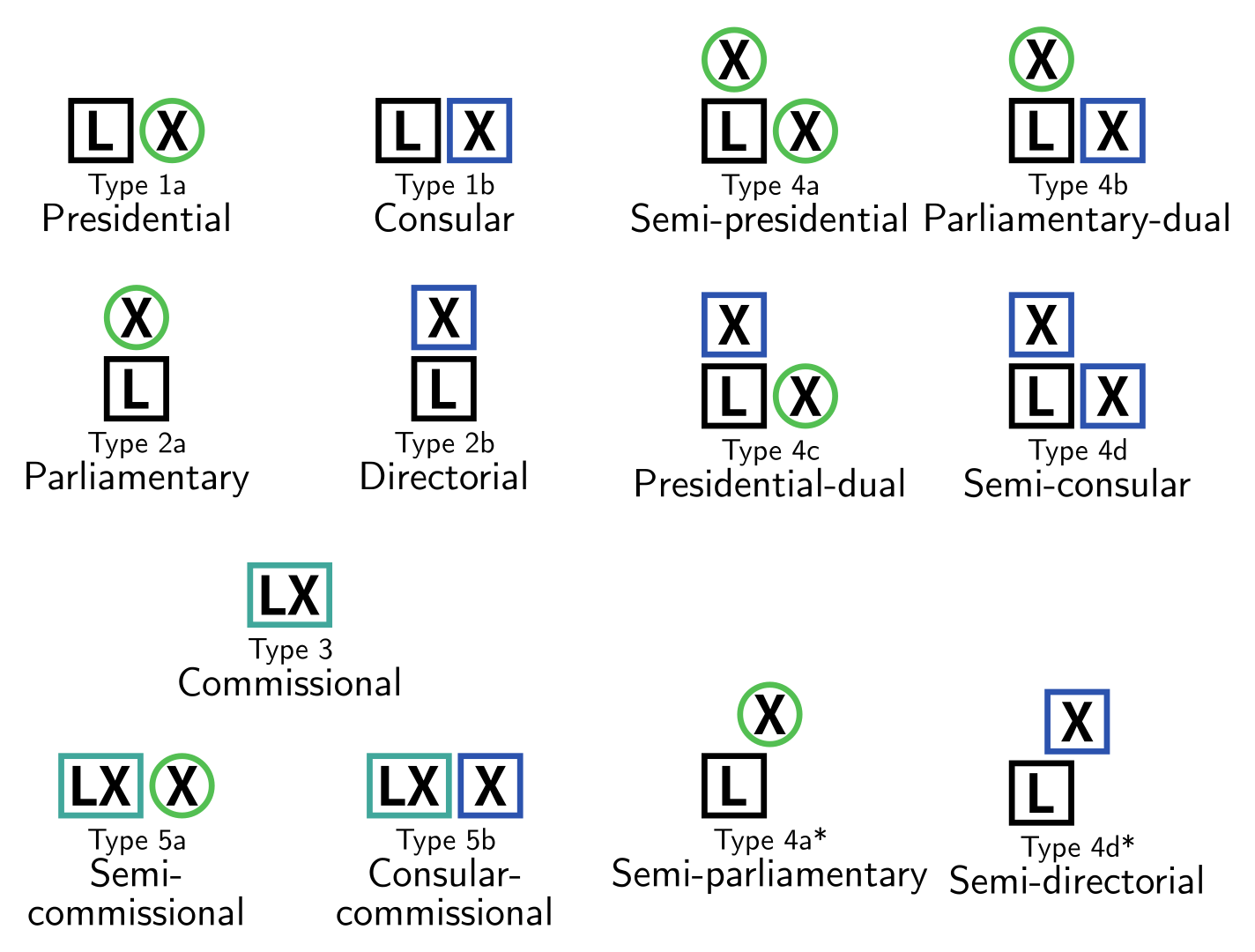

With all this aside, eleven forms of government can be enumerated:

Types 1a & 1b: The executive is elected separately from the legislature

- Type 1a (presidential): single-person executive (examples: presidential systems such as the United States, mayor-cabinet arrangements in the UK, mayor-council government in the US)

- Type 1b (consular): collegial executive (example: the cantons of Switzerland)

Types 2a & 2b: The executive is elected by the legislature

- Type 2a (parliamentary): single-person executive (examples: parliamentary systems such as the United Kingdom, leader-cabinet arrangements in the UK, council-manager government in the US)

- Type 2b (directorial): collegial executive (example: Switzerland)

Type 3 (commissional): The executive is merged with the legislature (examples: committee system in the UK used in Brighton and Hove, city commission government in the US)

Types 4a, 4b, 4c, 4d: The executive is in two parts, one elected by the legislature, one elected independently

- Type 4a (semi-presidential): executive split between a single person executive elected by the legislature and a single person elected independently (example: semi-presidential systems such as France)

- Type 4b (parliamentary-dual): executive split between a single person elected by the legislature and a council elected independently (no example)

- Type 4c (presidential-dual): executive split between a council elected by the legislature and a single person elected independently (no example)

- Type 4d (semi-consular): executive split between a council elected by the legislature and a council elected independently (no example)

Types 5a, 5b: The executive is in two parts, one merged with the legislature, one elected independently

- Type 5a (semi-commissional): executive split between the legislature and a single person elected independently (no example)

- Type 5b (consular-commissional): executive split between the legislature and a council elected independently (no example)

Alternatives

Given that all these rules are compromises between abstraction and complexity, they can be loosened to give more possibilities.

Multiple dependency links

This is the looser version of Caveat 1.

In semi-parliamentary systems (Duverger’s definition), a person may be dependent on multiple institutions. This is considered by saying that two institutions with the same composition and powers can actually be a single one, that is “elected” (is dependent on) two other institutions.

This adds two more types:

- *Type 4a (semi-parliamentary)**: single-person executive elected independently from the legislature but reliant on it (example: Israel between 1996 and 2001)

- *Type 4d (semi-directorial)**: council executive elected independently from the legislature but reliant on it (no example)

Note how I blended the meanings of “elected by” and “dependent on”. This is explained by abstracting away their difference: a president being elected by an assembly for a fixed-term, and a prime minister receiving the same assembly’s confidence that can be pulled back at any time, are in fact quite similar: both rely on that assembly to get or maintain/renew (if no term limits) their position, whatever the term length.

Confidence chambers

The other assumption I did not mention before is that every person or council has a role (executive, legislative, or both). If we add the possibility that people or council may exist only with the role to elect other people or councils, the amount of possible forms of government grows very quickly: if we only allow up to one electing council in a row maximum, we get to 60 forms of government. Most of them are either electoral colleges or “confidence chambers” in the style of Gangof’s parliamentarism, and thus have little actual utility to characterize forms of government.

Comments

No comments yet. Be the first to react!